La Ciociaria

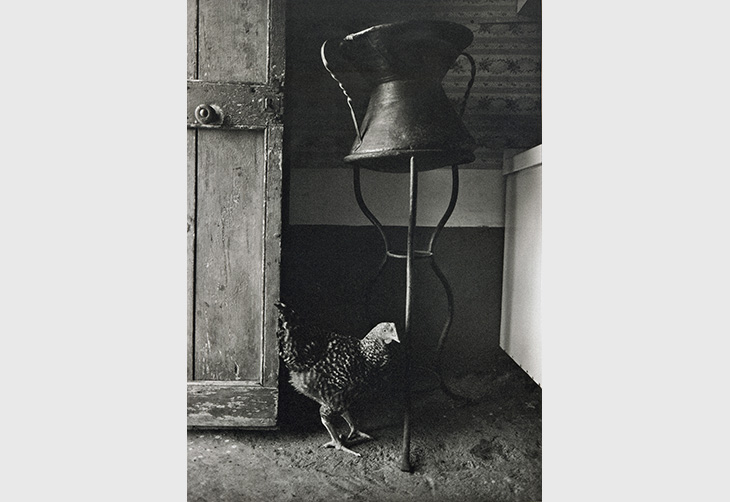

La Ciociaria is the region south of Rome where I lived in the 1970s and 1980s. Ciociaria means “those who wear ciocie”, i.e. the thong sandals dating back to Roman times. By the 1970s, only a handful of shepherds endured in the mountains, herding goats and buffaloes. During the winter a few would return to their villages down in the valleys. For twenty years I climbed mountains, scaled rocky ridges, and walked sentinels traced out by centuries of transhumance, documenting the most intimate emotions and rituals of men, women and children in isolated hamlets and in villages perched on hilltops. Attilio Quinto was one of the Ciociari with whom I shared time during these countless treks. When he was no longer able to climb the steep slopes, he gave me the ‘key’ to his 11th-Century stone shelter. From this base I photographed wood carvers and basket makers, musicians and brigands, cheese makers and the production of mozzarella from buffalo milk, to popular feasts and processions that are both Christian and pre-Christian in tradition, some dating back many thousands of years. I became immersed in their world as a participant rather than an observer, never conscious that the way of life there would soon undergo radical change or even disappear: most villages in Ciociaria have survived centuries of war, invasions, plague and, more recently, rape and other forms of cruelty by French North African troops at the end of WWII. I was also fascinated by the enormous gulf between rural ways and life in the city of Rome, barely 70 km further north.

Monte Lepini became my refuge in the 1990s during heart-breaking years of sadness, loss and anger. I used to make the two-hour journey on foot, carrying a backpack of food and wine, pen and paper, and a camera. From my shelter I wrote about my loneliness, a bitter marriage and a yearning to return to Africa. I cooked pheasant or guinea fowl (raised by me on the farm) in an African three-legged iron pot with wild sage and thyme collected on the mountain slopes. I waited for the shepherds’ echoing calls from one mountain ridge to another – a time to meet at the fontana where the goats could take a drink and where we could share a meal of marzolino goat’s cheese, chicory, wild mushrooms and bread. I kept bottles of home-made wine hidden in a secret grotto that Attilio had revealed before his retreat. It was also at Monte Lepini that I found solace and reassurance after some difficult journeys into the Atlas Mountains of Morocco (where I worked on my book Imazighen), and I won back sufficient courage to make important changes in my life.

In 2010, for the occasion of my exhibition C’era Una Volta la Ciociaria, I presented 150 photographs (as well as many utensils and artefacts seen in my photographs) to the Municipality of Amaseno, one of the towns in Ciociaria. Without my knowing, the Mayor had brought together several of the former shepherds who were in my photographs, including Attilio – who gave me a pair of ciocie that I had asked him to make but never had time to collect. He knew I would return some day. And I did, 24 years later! Like old times we later danced in the piazza to local folk music played on the zampogna (double chantered pipes using goat skin bags), ciaramella (from the oboe family) and an organetto (an Italian folk instrument much like the accordion).

In the summer of 2013 – now challenged by cancer and its debilitating treatment – I returned to my retreat, not sure whether I would find it still standing or whether I would even be strong enough to climb the rocky sentinels. From the dilapidated rooftop of what was once my stone shelter, I made notes for my memoirs. But more important, I came to the realization that I needed to let go...

Margaret Courtney-Clarke, 2013